For non-governmental organisations (NGOs), photography is one of the most powerful tools for advocacy and fundraising. A single image can bridge vast distances, foster deep empathy, and inspire action in ways that text and data alone cannot, tapping into the psychology behind why we’re drawn to dramatic scenes. It can give a human face to complex issues, celebrate resilience, and document the tangible impact of an organisation’s work.

Yet, this power comes with a heavy responsibility. When the subject is a human being, especially one in a vulnerable situation, the camera can become an instrument of misrepresentation if not handled with profound care. A photograph can either uphold a person’s dignity or strip it away; it can challenge stereotypes or reinforce them. This article explores the dual nature of photography in NGO campaigns, delving into the best practices that ensure images serve not only the campaign’s goals but, more importantly, the people at the heart of the story.

The Power and Responsibility of NGO Photography

There is no denying the profound impact a photograph can have on the public consciousness. History is punctuated by images that have catalysed social change. The haunting photographs by Lewis Hine of child labourers in the early 20th century were instrumental in reforming labour laws in the United States. More recently, the heart-wrenching image of Aylan Kurdi, a young Syrian refugee, washed ashore on a Turkish beach, forced a global conversation about the refugee crisis that statistics and reports had failed to ignite. For NGOs, this power is the bedrock of visual campaigning. A compelling photograph can tell a story in an instant, transcending language barriers to communicate need, resilience, and hope. It can move a potential donor from passive awareness to active support, drive signatures on a petition, and provide undeniable evidence of an organisation’s impact for grant reports and stakeholder communications. The rise of social media has only amplified this effect, allowing a single, powerful image to reach millions within hours, creating movements and mobilising support on an unprecedented scale.

However, this same power can be deeply problematic when wielded without ethical consideration. The sector has long grappled with the damaging legacy of what is often termed ‘poverty porn’, the use of shocking or pitiable images of suffering to elicit guilt and donations. While potentially effective in the short term, this approach is corrosive. It reduces complex individuals to one-dimensional victims, perpetuating harmful stereotypes of helplessness and dependency. It can reinforce a paternalistic narrative of outsiders saving communities, ignoring the agency and capacity of the people themselves. This can lead to public desensitisation, where audiences become numb to a constant barrage of suffering. Even the well-intentioned counter-narrative, the ‘smiling African child,’ can be a form of oversimplification, masking the systemic issues that necessitate aid in the first place. The challenge, therefore, is to harness the emotional power of photography without falling into the trap of exploitation, to tell stories that are both compelling and true to the dignity of the subject.

The Ethical Compass: Consent, Dignity, and Collaboration

Navigating the ethical minefield of humanitarian photography requires more than good intentions; it demands a robust framework built on the principles of consent, dignity, and collaboration. Many leading organizations and confederations, such as CONCORD and Bond, have developed codes of conduct to navigate these complexities. These frameworks emphasize a rights-based approach, with excellent resources like Bond’s guide on Putting the people in the pictures first urging organizations to see people as partners in the storytelling process. This framework must guide every decision, from the moment a photographer raises their camera to the final selection and distribution of an image. It is a fundamental shift from seeing people as subjects to seeing them as partners. This approach not only protects the individuals being photographed but also results in more authentic and powerful campaign materials. The guiding principle should always be ‘Do No Harm,’ a commitment to ensuring that the act of telling a story does not inflict further pain or compromise the safety and dignity of the individuals involved.

Beyond the Shutter Click: The Centrality of Consent

Informed consent is the absolute, non-negotiable cornerstone of ethical photography. It is not merely a box to be ticked or a signature on a form; it is an ongoing dialogue built on respect and transparency. True consent means clearly explaining, in a language the person understands, who you are, which organisation you represent, how their photograph will be used, and the potential impact. For example, a photographer might say: ‘Hello, my name is [Name] and I am with [NGO Name]. We are sharing stories about our community health program. Would it be okay if I took your photograph for our website and annual report to help show others the work we do? Your name will not be used if you prefer, and you can ask me to stop at any time.’ For children or other vulnerable individuals, this process is even more critical. Consent must be obtained from a parent or legal guardian, and the child’s own willingness and comfort should be continually assessed. If a child seems hesitant, the camera should be lowered immediately, regardless of parental permission. It is vital to respect a person’s right to say no, or to change their mind later, without any pressure.

Crafting a Narrative of Dignity Not Pity

Once consent is established, the photographer’s creative and ethical task is to craft a narrative that upholds dignity. This begins with collaboration. Ask people how they wish to be portrayed. They may want to be photographed in a particular setting that holds meaning for them, or be shown performing an activity that highlights their skills and strengths rather than their needs. The goal is to capture the wholeness of their humanity. This means actively working to subvert stereotypes. Instead of focusing solely on hardship, look for moments of resilience, joy, and community. Show people as active participants in their own lives, not passive recipients of aid. Composition, lighting, and moment are all tools that can be used to this end. A low angle can convey strength, while soft, natural light can create a sense of respect. A tangible way to build trust is to offer an immediate print of the photograph to the person. This simple gesture can transform the interaction from a transaction into a respectful exchange, showing that their participation is valued beyond its use for the campaign.

From Field to Frame: The Practical Workflow of an Ethical Campaign

Translating ethical principles into practice requires a structured and intentional workflow. Every successful and responsible photography campaign is built on a foundation of meticulous planning, clear communication, and robust systems for managing the resulting assets. This ensures that the organisation not only captures powerful images but also manages them in a way that honours the agreements made with the people in them. From developing an internal policy to archiving photos securely, each step is an opportunity to reinforce the organisation’s commitment to ethical storytelling.

Planning and Preparation as the Foundation of Success

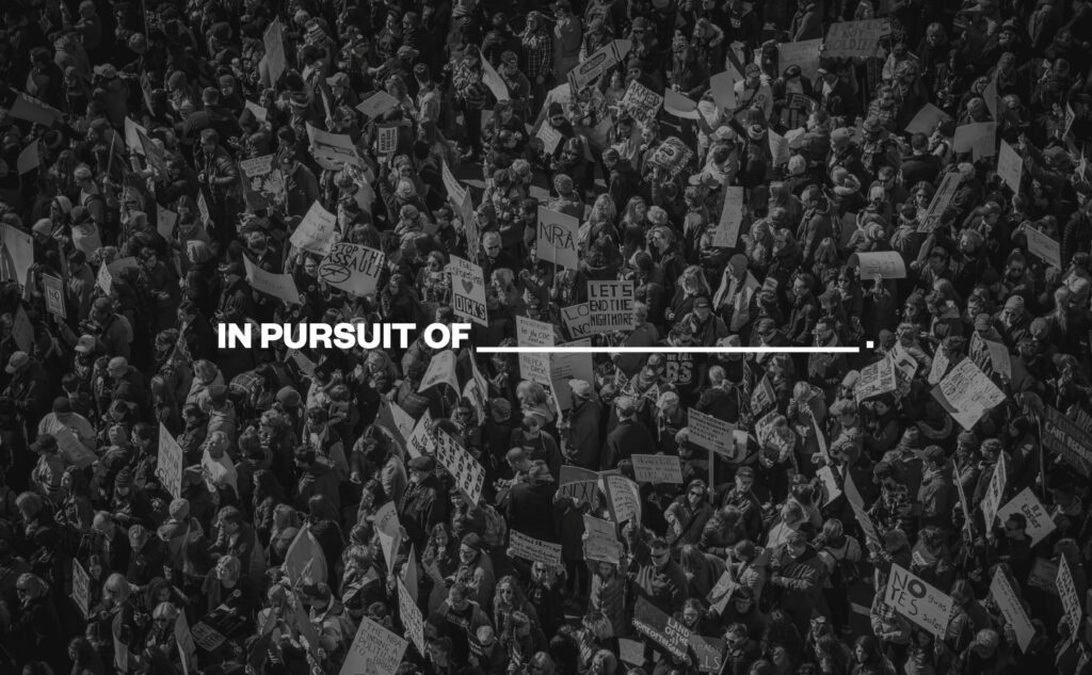

Great photography rarely happens by accident. It begins with a clear and comprehensive brief. Before a photographer enters the field, the NGO should have a well-defined photography policy that outlines its ethical commitments. This policy should inform a specific ‘shot list’ for the campaign, detailing not just the types of images needed but also the narrative and emotional tone the organisation wants to convey. For example, a campaign focused on advocacy might require powerful, galvanising images like the one below, which captures the energy of collective action. When working in unfamiliar cultural contexts, hiring a local ‘fixer’ can be invaluable. This individual can help navigate cultural nuances, build trust with the community, and facilitate the consent process. The investment in planning pays dividends in the form of images that are not only beautiful but also purposeful and respectful.

Managing the Visual Assets: Archiving and Distribution

The responsibility does not end when the photos are taken. Proper management of visual assets is a critical aspect of ethical practice. This starts with accurate record-keeping. Each image should be accompanied by detailed and truthful captions that provide context. Digital manipulation should be minimal and never alter the fundamental truth of the photograph. Most importantly, consent forms and usage rights must be meticulously tracked. The logistical challenge of tracking these details can be immense. This is where specialized platforms become essential for maintaining integrity. For organizations looking to upgrade from basic spreadsheets, comprehensive management software from a provider like NGO Online offers a vital solution. Such tools help centralize information, linking photos directly to project data, grant requirements, and signed consent forms, which is crucial for improving operational effectiveness and ensuring donor compliance. Furthermore, consider how the narrative will adapt across different platforms. While a series of photos might tell an episodic story of progress on Facebook, a short video where the subject speaks for themselves can be more powerful on YouTube. The medium may change, but the ethical commitment to dignity and consent must remain constant.

The Enduring Image: A Legacy of Respect

In our hyper-visual world, an image can feel fleeting, just another tile in an endless scroll. But for the person in the photograph, its existence can be permanent. A single picture can follow them for the rest of their lives, shaping how they are seen by their community and even how they see themselves. As photographers and communicators, we must confront this reality. The goal of our work cannot simply be to create a successful campaign or a viral image. We are creating a permanent record, an archive of human experience. The true measure of our work is not just the funds it raises or the awareness it generates, but the legacy it leaves behind. Is it a legacy of respect, truth, and empowerment? Or is it one that, however unintentionally, contributes to a narrative of pity and simplification? The choice is ours to make with every click of the shutter. It is a profound privilege to be entrusted with someone’s story, and our most sacred duty is to honour that trust with every image we create and share.